| 1900Alabama’s total population was listed in the census at 1,828,697.

The number of business establish- ments in the state was 5,602, an increase in 10 years of 88.2 percent. Capital invested totaled $70,370,081, an increase of 52.6 percent. There were 52,902 wage earners, an increase of 69.9 percent. The value of land and plants was $24,987,473, an increase of 96.5 percent.

The 11 leading industries in the state, in the order of the value of finished products, were

Iron and steel,

Lumber and timber products,

Cotton goods,

Foundry and machine shop products,

Cars and general shop construction and repairs by steam railroad companies,

Coke,

Flouring and gristmill products,

Cottonseed oil and cake,

Fertilizers,

Cotton ginning,

Leather—tanned, curried, and finished.

1909

The seven principal industrial cities of the state in 1909 in order were:

Birmingham

Bessemer

Montgomery

Mobile

Anniston

Selma

Gadsden

Cotton was one of the most impor- tant factors in the economy of Alabama, both from the standpoint of agriculture and manufactures. In 1909 cotton accounted for 60.3 percent of total crop values in the state. The number of acres in cotton was 3.7 million, exceeding the acreage of corn, which ranked second, by 1.6 million acres. In fact, the cotton acreage exceeded the total acreage of corn, oats, wheat, and rye combined and constituted 38.5 percent of all the improved land in the state. Alabama was third on the list of cotton-growing states, behind Texas and Georgia.

In 1909 there were 81,972 persons employed in manufacturing, as compared to 67,884 in 1904.

One of the most remarkable developments of this decade was the enormous growth of fertilizer manufacturing in the state. The value of fertilizer products increased 174.4 percent between 1904 and 1909. For the same period the value of manufactured cotton goods rose 32.5 percent.

1910

Alabama’s population topped two million for the first time. On Census Day it was 2,138,093.

1913

October 3. The U.S. Congress passed the income-tax law.

1915

Alabama citizens and corporations paid a total income tax, during the fiscal year ending June 30, 1915 of $261,760. There was $84,633 reported by individuals and $177,127 by corporations. There were 1,908 reporting individuals.

1917

January 17. The Virgin Islands were purchased by the United States from Denmark for $25 million.

March 2. Puerto Rico became a part of the United States via the Jones Act.

March 15. Czar Nicholas II of Russia abdicated.

April 6. The United States declared war on Germany.

1919

The average annual wage in Alabama was $924.

1920

Alabama’s population had grown by 210,000 in ten years. The Census count was 2,348,174.

Life expectancy in the United States was 53.6 years for men and 54.6 years for women.

Tuberculosis was the second leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease.

Eggs cost 68 cents a dozen; milk was 17 cents a quart; bread was 12 cents a loaf; round steak was 42 cents per pound; oranges were 63 cents per dozen; coffee was 47 cents per pound.

Sports. The Boston Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees for $10,000, plus a $385,000 loan. Ruth hit 54 home runs and asked that his salary be doubled to $20,000.

In the longest game ever, 26 innings, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Braves tied, 1-1.

The American Professional Football Association, the first organized pro league, was formed in Canton, Ohio, with Jim Thorpe as president. Franchises were $100. Games were poorly attended.

The Olympics were held at Antwerp, Belgium.

Bill Tilden was the first American to win at Wimbledon.

1929

Quotes Before the Crash

“This has been a twelvemonth of unprecedented advance, of wonderful prosperity…. If there is any way of judging the future by the past, this new year may well be one of felicitation and hopefulness.” —Herbert Hoover

“If a man saves $15 a week and invests in good common stocks,…at the end of 20 years, he will have at least $80,000, and… $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich.” —John T. Raskob, former top executive, General Motors, and chairman, Democratic National Committee

Quotes After the Crash

“Any lack of confidence in the eco- nomic future of the basic strength of business in the United States is foolish.”—Herbert Hoover

“[There is just] a little distress selling on the Stock Exchange.”—Financier Thomas Lamont, after leaving the offices of J.P. Morgan

Total income in the State of Alabama came largely from six counties: Jefferson, Mobile, Montgomery, Etowah, Tuscaloosa, and Calhoun.

1931

Agriculture was the predominant occupation in Alabama, with 48 percent of total workers employed in this field. Manufacturing employed 18 percent of the workforce.

Jefferson County’s labor force consisted of slightly more than 31,000 workers.

Alabama’s coal production was 18,975,000 net tons, 3.3 percent of total production for the United States.

The percentage of persons in Alabama age 10 to 19 who were gainfully employed was 29.6 percent. Forty-one percent of persons over 65 remained employed.

The average annual wage in Alabama was $727.49, down from the pre- Depression average.

1935

Alabama ranked fifth in the nation in textile manufacturing. The cotton industry had remained strong while other industries were more adversely affected by the Depression.

August. The two houses of the state legislature passed a resolution requesting the School of Commerce of the University of Alabama to study the effects, per percentage, of a state sales tax.

Nationally, one out of four house- holds was on relief and 750,000 farms had been foreclosed since 1930.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed half a million young men in conservation projects across the country for which they earned $40 a month.

The WPA took over work relief. A total of 8 million people built schools, libraries, bridges, roads, hospitals, and sewage systems. Boondoggling entered the national vocabulary when some critics called relief work busy work for the unemployed.

Americans consumed 50 million chickens a year and paid more for poultry than red meat.

Counterfeiting had increased 400 percent since the Depression began. |

1940(National Averages)

Types of Employment and Percentage of Total Employed

Agriculture 39.6 %

Manufacturing 17.4 %

Personal Services 10.6 %

Trade, wholesale and retail 10.1 %

Professional and Related

Services 4.9 %

Transportation,

Communication, and

Public Utilities 4.3 %

Government 2.4 %

1942

Business in Alabama saw a substantial increase due to the war. This was led by a large increase in cotton production. Building contracts increased 250 percent between 1940 and 1942. Retail sales also increased.

1944

Total income payments in Alabama increased between 1939 and 1944 at a much more rapid pace than in the United States and the Southeast. The percentage increase was 171 for Alabama, 110 for the United States, and 147 for the Southeast.

1948

The condition of state funds for the budget were reported to be as follows:

The outlook for the general fund is dismal.

The highway fund is under continuous pressure.

Appropriations from the fund for the State Board for Agriculture and Industry will absorb current receipts and the opening cash balance.

The Education Trust Fund is in excellent shape in terms of current appropriations and available receipts.

Other funds are in from good to excellent condition.

1950

Alabama’s census showed a population topping the three million mark for the first time: 3,061,743.

1955

The idea of a guaranteed wage was discussed in an effort to satisfy workers’ desire for employment security.

Alabama’s personal income average was 65 percent of the national average.

1956

Electronic machines were first used in businesses to help manage and operate business establishments.

The estimates of timber resources needed for the year 2000 ranged from 79 to 105 billion board feet, or from 67 to 122 percent of 1956 levels.

1960

The median per capita income of an Alabama resident averaged $3,937.

1961

Alabama, along with the rest of the United States, went through the trough of a mild postwar recession. The economy also experienced a slight recovery.

1966

The economy of Alabama was growing both internally and externally due to “(1) a high proportion of big-name industry with both resources and needs for expansion, (2) liberal representation of growth companies, and (3) apparently great enough confidence in the Alabama outlook to make these companies want to deepen their roots in the Alabama soil.”

The state’s principal industries had gone from steel and paper to autos and high-tech.

1970

The median per capita income of an Alabama resident averaged $7,266.

Thirty percent of Alabama’s income was generated in District 3, which contained Birmingham and Jefferson County.

A moderate standard of living for an urban family of four cost, nationally, $10,664.

1974

From 1970-1977, the average CPI inflation rate for the United States was 6.5 percent, with a high of 11 percent in 1974.

1976

A moderate standard of living for an urban family of four cost $16,236.

In 1976, the push towards consumer- ism, the protection of the consumer, gathered momentum and protection legislation was introduced at the state level.

1980

The percentage of Alabama residents age 65 and over grew from 9.5 percent in 1970 to 11.3 percent in 1980.

1987

Alabama’s population pushed through the four million mark.

1993

On September 30, 1993 Mercedes- Benz announced its plan to build a plant in Alabama. The incentives given to the automaker were seen as outrageous by many, but worthwhile by others.

At the end of 1993, the Alabama housing affordability index illustrated the fact that a family earning the median income in Alabama, $33,317, had 162 percent of the income needed to qualify for conventional financing on the statewide median priced home of $77,525.

1994

Alabama’s average annual pay was $22,786, compared with the U.S. average of $26,632.

1995

Federal data suggested that Alabama attracted new residents from every state, while generally keeping Alabamians at home. This depicted a significantly different trend from the outmigration of the eighties. The new inmigration data indicated a resurgence of the Alabama state economy.

1996

Retail sectors in Alabama, while experiencing strong growth in sales, trended toward fewer, larger stores. The only sector to see a decline in sales was the auto industry.

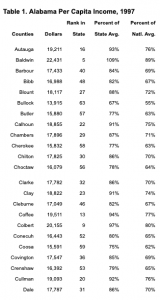

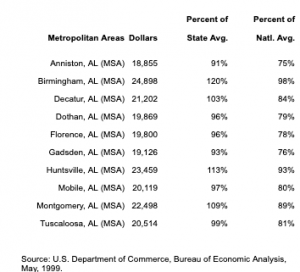

1997

The idea of a state lottery was initialized. The political debate framed the issue as a decision between religious views and state revenues. At this time, 66.8 percent of Alabamians supported a state lottery.

The effect of the decline in birth rates in the 1970s caused labor shortages, wage pressures, and large turnover rates.

1998

Increasing exports for the state accompanied increasing Alabama prosperity. During this year, due to Mercedes M-Class exports, Alabama was expected to increase its exports by 25 percent. This large export increase was seen as a sign of progressiveness and global competitiveness. Political leaders assured the public that Mercedes aids in the attractiveness and reputation of the State of Alabama.

1999

May 6. American Honda Motor Corp announced plans to build a $400 million facility in the Talladega County town of Lincoln.

Sept 30. Alabama citizens and corporations paid income tax during the past 12 months of $2,488.2 million. Individuals paid $2,235.8 million, while corporations paid $252.4 million. Individuals paid 90 percent of the income tax, while corporations paid 10 percent. This was a sharp contract to 1915 when individuals paid 32 percent and corporations paid 68 percent. |