The New Economy: What is it and is Alabama ready?

Alabama is a participant in the “New Economy” of the 21st century where economic wealth and job creation are increasingly driven by ideas, innovation, and technology. This does not mean that most firms are manufacturing technology or delivering technology services—such firms accounted for about 11 percent of U.S. GDP in 1999. Rather, most firms are organizing their work around some aspect of technology. Investment in information technology is a major factor in enhancing business operations and increasing productivity throughout the U.S. economy.

The demands of a technology-driven economy are in some ways the same, but in many ways quite different from those of the old industrial order. Location decisions are influenced in part by traditional factors that affect the cost of doing business including tax rates or incentives, compensation costs, land and office costs, energy costs, capital costs, and the business climate, areas as a whole where Alabama can do well. But technology-oriented firms also emphasize the availability of a trained and educated workforce, proximity to excellent higher educational facilities and research institutions, an existing supplier network, access to venture capital, and a good quality of life. While workforce demands tend to rule out many rural areas, an emphasis on quality of life may increasingly result in more activity outside the nation’s major urban centers. Although parts of Alabama have much to offer in many of these areas, availability of an adequate trained and skilled workforce is a major weakness. Recent reports indicate that even in Huntsville, home to Alabama’s highest concentration of high-tech industries, firms are having a hard time finding college-educated engineers and technical workers to fill available jobs. Shortages have been noted in Birmingham and Montgomery as well.

Where are the citizens of Alabama today?

Workforce—On the key factor of an educated working age population, we lag behind. In 1998, 78.8 percent of Alabamians 25 years old and over had completed high school, ranking the state 42nd. With 20.6 percent of these residents completing a bachelor’s degree or higher, the state’s 1998 ranking was 38th. Many of today’s high-tech jobs require a college education and recent projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that jobs needing at least an associate’s degree will increase more rapidly to 2008 than jobs requiring less education. Of course, educational attainment is not evenly dispersed across counties—in 1990, 37 of Alabama’s 45 rural counties had fewer than 60 percent of adults with a high school education. On the other hand, Alabama’s worker training initiatives through the Alabama Industrial Development Training Program (AIDT) have been a significant factor in attracting major firms like Mercedes, Boeing, and Honda.

Computer Literacy—With the development of the Internet and the declining cost of personal computers, more and more Americans have electronic access to the information economy. According to the National Telecommunications Information Administration, by the end of 1998 over 40 percent of U.S. households owned computers and 25 percent had Internet access. However, the South as a region is behind, creating what has been termed a “digital divide.” Alabama ranked just 46th, with 34.3 percent of households owning computers in 1998. It earned a ranking of 39th for 21.6 percent of households with Internet access, better than eight other southern states. Actual usage is of course higher, as many access computers and the Internet at work, school, and community centers.

Where is Alabama’s high-tech economy today?

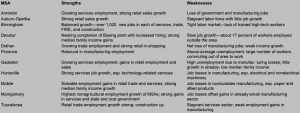

Certain areas of Alabama are heavily involved in high-tech manufacturing and services. A 1999 study by the Milken Institute asserts that the high-tech sector is boosting the long-term growth path of the U.S. economy. Focusing on the nation’s metro areas, they conclude that high-tech activity explains 65 percent of the differences in output growth among metro areas during the 1990s. In their definition of “tech poles”—metro areas that assert the strongest technology gravitational pull—Huntsville ranked 50th and Birmingham ranked 57th. Huntsville ranked 23rd on the percentage of total real output in high-tech in 1998 at 16.1 percent, with high-tech employment of 34,380. Further breaking down high-tech industries, the Institute ranked Huntsville high on several indices: 9th on overall concentration of high-tech services; 3rd on output of guided missiles, space vehicles, and parts; 7th on computer and data processing services; and 2nd on engineering and architectural services output. Birmingham also showed its high-tech strength with the 2nd highest concentration of telephone communications services among all U.S. metro areas and a 15th place ranking on overall high-tech services. High-tech services accounted for 9.2 percent of total area output and employed 21,140 in 1998.

Business Alabama Monthly’s December 1999 ranking of the state’s top 100 technology firms confirms these area concentrations—the Huntsville MSA claimed 45 of the 100, followed by Birmingham with 21. Huntsville was home to two of the nation’s top 150 electronics companies in a 1999 ranking by Electronic Business—SCI Systems at number 52 and Intergraph at 172. The state is a major player in contract manufacturing, with SCI Systems the largest in the nation; Avex Electronics of Huntsville 8th largest; and Mid-South Industries of Gadsden 39th. The Huntsville and Montgomery MSAs made the list of the top 20 U.S. sites for electronics companies in the 1999 Electronics Industry Year Book. Montgomery is home to almost 100 information technology firms focusing primarily on software development.

Support for New Technology Ventures

Incubators—Many fledgling high-tech companies must be nurtured in their early stages. Incubators have been growing in number with about 600 nationwide in 1999 compared to 12 in 1980. Two Alabama groups made Digital South’s 1999 list of major incubators: the Office for Advancement of Developing Industries (OADI), started in Birmingham in 1986, currently with 25 tenants and a $1 million budget from UAB; and the Business Technology Development Center in Huntsville, founded in 1997 and housing five tenants in 1999 with a $500,000 budget from NASA, TVA, and state and city grants. OADI has been instrumental in the development of Birmingham’s biotechnology cluster.

Venture Capital—Venture capitalists provide the finances to develop new firms. The MoneyTree U.S. Report’s recent survey of venture capital firms found venture capital investments totaling $35.6 billion nationwide in 1999, up 150 percent from 1998. Ninety percent of the 1999 venture capital was directed at technology-based companies. Software firms captured 18.5 percent of the total; telecommunications, 14.7 percent; and business services, 12.8 percent. With $59.2 million in venture funds invested in the state in 1999, Alabama ranked 28th.

Venture Capital Investments

(millions of dollars)

Source: PriceWaterhouseCoopers, Moneytree U.S. Report.

IPOs—Most IPOs are spawned from the high-tech and Internet sectors, making them a barometer of an area’s technology growth. Alabama has had few IPOs in recent years. In addition, over a dozen of the state’s publicly traded companies have been bought out or folded over the last several years. And there do not appear to be many companies than might be ready to go public in the next few years. However, innovation as measured by patents awarded has accelerated during the last several years, with UAB alone tallying 45 for 1999 and the first quarter of 2000.

Where do we rank on “The State New Economy Index?”

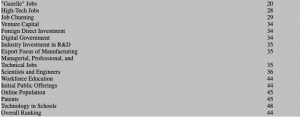

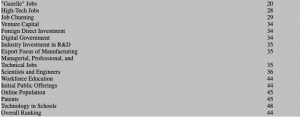

Alabama’s “New Economy Index”

Ranking by Selected Components

Source: Progressive Policy Institute.

“The State New Economy Index,” compiled by the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) in 1999 for their “Technology and New Economy Project,” ranks Alabama 44th among the 50 states on a composite of variables that contribute to successful economic transformation in a technology-based environment. These variables represent five factors: knowledge jobs, globalization, economic dynamism, transformation to a digital economy, and technological innovation capacity. Alabama received its highest rankings on jobs in “gazelle” companies (companies with revenue growth of at least 20 percent for four straight years), high tech jobs as a share of total, and job churning (a measure of business start-ups and failures). It came up especially short on technology in schools, online population, IPOs and patents, and workforce education (a weighted measure of postsecondary education). Massachusetts ranked first on the index, followed by California and Colorado. Mississippi, Arkansas, and West Virginia had the lowest index scores.

According to the Institute, low costs, tax abatements and other financial incentives no longer insure success. “In the New Economy, states’ economic success will increasingly be determined by how effectively they can spur technological innovation, entrepreneurship, education, specialized skills, and the transition of all organizations—public and private—from bureaucratic hierarchies to learning networks.” The study also offers policy strategies for states:

- Co-invest in the skills of the workforce

- Co-invest in an infrastructure for innovation

- Promote innovation and customer-oriented government

- Foster the transformation to a digital economy

- Foster civic collaboration.

How can Alabama move into the mainstream of the “New Economy?”

Given Alabama’s economic history, the socioeconomic makeup of our people, and a development strategy traditionally focused on low costs and abundant natural resources, it is not surprising that we lag in readiness. According to the PPI, this should be seen as a challenge: “While history shapes the hand a state is dealt, public policy determines how the hand is played.” In key aspects of business, Alabama is headed in the right direction.

A number of statewide initiatives and organizations are geared toward encouraging the growth of high-tech industry in Alabama. The Alabama Semiconductor Alliance, formed by the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama (EDPA), has been at work promoting Alabama sites suitable for the semiconductor industry. And the Microelectronics Education Consortium, an organization of 13 two-year colleges and EDPA, is working to increase the readiness of Alabama’s workforce for jobs in the microelectronics and semiconductor industries. The Alabama Technology Network, a collaborative effort of The University of Alabama system, Auburn University, selected two-year colleges, and EDPA, is available to help existing industry make the transition to the “New Economy.” In addition, the newly-formed nonprofit Alabama Information Technology Association is promoting high-tech companies and providing networking opportunities for inventors and investors.

On the governmental side, Governor Don Siegelman’s Commerce Commission has proposed legislation designed to support the growth of small, high-tech companies, which often cannot benefit from traditional incentives or tax breaks. A state tax credit for 80 percent of research expenditures above a base level, including research and development contracts with state universities, would be given to help fledgling high-tech companies get on their feet. The credits could be sold to other firms to raise capital if the firm did not owe taxes. The state is also contemplating incentives to help lure a semiconductor manufacturer to Alabama.

Some areas of the state are doing well in the knowledge- based economy. But urban and rural Alabama must both move forward if the state as a whole is to flourish. A well-educated citizenry with up-to-date work skills is fundamental to attracting and growing more technology-based jobs. Efforts to build Alabama’s high-tech sector will fall flat if we cannot provide these industries with the engineers, computer scientists, and other technologists they need.

References

Many of the reports, publications, and organizations referred to in this article can be accessed over the Internet. Click here to access a list of web sites that relate to the New Economy.

Carolyn Trent