A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the New Alabama Immigration Law

- July 24th, 2019

Samuel Addy, Ph.D. and Ahmad Ijaz

Center for Business and Economic Research

Culverhouse College of Commerce and Business Administration

The University of Alabama

September 2010

Summary

This report presents preliminary macroeconomic impact estimates of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill on Alabama for 2010. The purpose is to provide some sense of the effect of the disaster on the state and to provide information that can help the state make claims for resulting lost tax revenue in the first year. We consider only macroeconomic impacts and not (i) micro impacts that businesses and individuals can use for making claims or (ii) environmental, ecological, and noneconomic quality of life impacts that contribute to determining the full effects of the disaster.

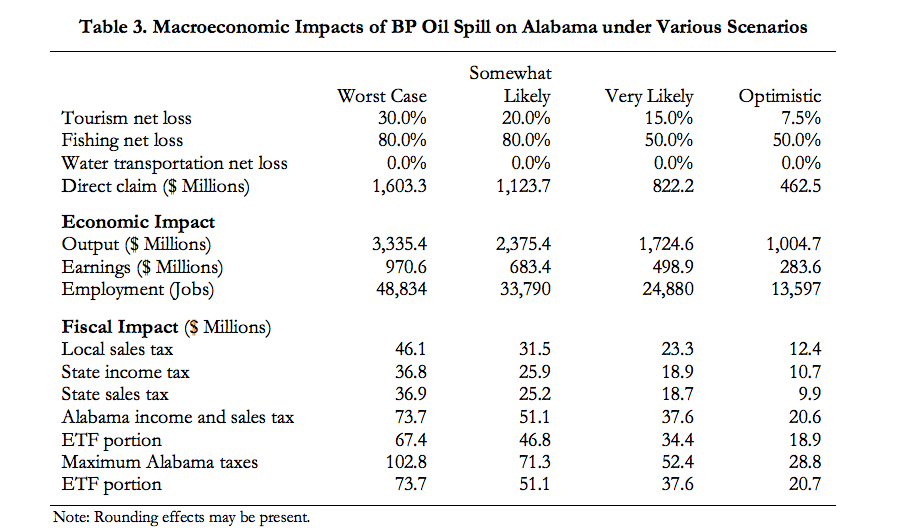

Four scenarios for impact estimates are considered in a sensitivity analysis to account for the uncertainty regarding such disaster estimates, especially since the year is not yet over. The scenarios involve different loss effects on tourism and fishing activities in the state from year 2008 levels. The worst case assumes 30 percent and 80 percent annual net loss on tourism and fishing, respectively; the optimistic case involves corresponding losses of 7.5 percent and 50 percent.

In the worst case the oil spill results in losses of $3.3 billion in Alabama economic output, $971 million in earnings, and nearly 49,000 jobs for 2010. Individuals and businesses could make $1.6 billion in claims and state and local governments could make a collective $149 million claim for lost tax revenues. The optimistic case results in (i) losses of about $1.0 billion in economic output, $284 million in earnings, and 13,600 jobs and (ii) claims of $463 million for individuals and businesses and $41 million for state and local government.

The oil spill’s effects are expected to last a number of years. Future year impacts will depend on additional information gained about the nature of the spill and the response and their combined environmental/ecological and quality of life effects. Such information will reduce the uncertainty regarding the disaster’s 2010 and subsequent years’ macroeconomic impacts.

Introduction

On April 20, 2010 the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico and resulted in 11 deaths, 17 injured, and a gush of about 53,000 barrels of crude oil per day from the seabed. Response to the spill involved containment, dispersal, removal and some burning, and a moratorium on deep offshore drilling activities. The gushing oil was stopped on July 15, 2010 by capping the Macondo well from which it was flowing. While the official flow rate has established the spill as the largest in U.S. history, there is still some uncertainty regarding the flow rate and total amount spilled. The U.S. government considers BP to be the responsible party for the disaster and has negotiated a $20 billion fund—which is not a cap and has the company’s U.S. assets as bond until fully paid for—to be used for purposes that include government response expenditures and claims from affected parties. There is significant uncertainty regarding the effects of this event and the response to it on the environment, ecology, economies, and people of the region. Determining the full impacts of the oil spill will take time, but there are immediate needs and claims that must be paid as the spill generated ongoing adverse effects on the economies and people of the region.

Comprehensive studies of the impacts of disasters such as the oil spill are complex because they must consider tangible and intangible effects on the environment, ecology, and quality of life along four dimensions (visibility, spatial, time, and distributional). The environmental and ecological effects need to be studied over time because of the dynamics of biological, chemical, and physical processes that help in determining effects on the environment, wildlife, food chain, toxicity issues, and ecosystems in general. Indeed, scientists are yet to fully account for the oil that gushed out, a question of inventory. Quality of life effects must cover economic impacts at micro and macro levels as well as social, cultural, psychological, health, political, and other issues. The visibility dimension demands considering direct, indirect, visible, and invisible impacts. The spatial dimension requires a look at distance, direction, and depth (surface, underwater, and above surface) impacts. The time dimension focuses attention on the pace and intensity of impacts. The fourth and final dimension, distributional, necessitates the determination of who and what systems are affected, how they are affected and by how much, and whether and how they should be compensated.

The motivation for this work comes from the need to understand somewhat the effect of the disaster on Alabama and to facilitate claims to recover losses due to the oil spill’s ongoing adverse effects on the state economy. The impacts presented in this report are just a small slice of the full impacts on Alabama and are preliminary macroeconomic impacts of the spill for 2010 only. We do not address (i) subsequent year impacts, (ii) micro impacts that businesses and individuals can use for making claims, or (iii) environmental, ecological, and noneconomic quality of life impacts. To deal with the uncertainty that disaster impact studies have to contend with, we use a sensitivity analysis on key variables—the net loss factors to tourism and fishing activities—that the oil spill causes. Our results provide some sense of the effect of the disaster on the state’s economy and hopefully provide an objective, reliable, and transparent analysis that the state can use to make a claim for lost state and local tax revenue in 2010.

Analysis and Results

Given that the oil spill was offshore and impacted coastal areas, one would expect that the spill’s direct and initial effects will be principally on tourism (which includes recreational fishing), commercial fishing, and water transportation. The interaction between these economic activities and the rest of the economy will result in indirect effects which must be combined with the direct effects to determine the macroeconomic impacts. This requires the use of economy-wide methodologies to determine impacts. Methods used in estimating economic impacts include econometric, economic base, computable general equilibrium (CGE), and input-output (I-O) models. Econometric and CGE models can be very costly and time-consuming to build and economic base models require a very detailed set of information that is sometimes not available. These three methodological approaches generate slightly smaller multipliers than I-O models because of assumptions on factors such as input substitution and optimization behavior by economic agents (consumers, businesses, and governments). The I-O modeling technique, which generates multipliers for economic activities of interest by focusing on economic interactions among all industries and all other economic transactions in a specified region, was used in this study. The multipliers used were obtained from the Regional Input-Output Modeling System (RIMS II), which is developed and maintained by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis. RIMS II is available for the nation, states, metro areas, and counties as well as for geographic areas for which enough information exists to construct a model.

To allow for uncertainty regarding disaster estimates and especially since we focus on estimates for 2010 while the year is not over, we consider four scenarios in a sensitivity analysis on losses to the directly affected economic activities. The scenarios involve different net loss effects on tourism and fishing activities in the state from year 2008 levels; we assume no losses for water transportation since we are unaware of any such reports, not even anecdotally. The base year of 2008 is the most recent year for which we could assemble a complete set of data for the analysis. The worst case assumes 30 percent and 80 percent annual net loss on tourism and fishing, respectively; the optimistic case involves corresponding losses of 7.5 percent and 50 percent. A “somewhat likely” scenario considers 20 percent tourism loss and 80 percent fishing loss and a “very likely” scenario looks at 15 percent tourism loss and 50 percent fishing loss. We use these net loss factors to determine the direct economic effects on Alabama tourism and fishing and then apply the RIMS II multipliers to generate impacts on state economic output, earnings, and employment.

Fiscal impacts are derived from the earnings impacts allowing for the fact that not all of the earnings impacts are sales or income taxable. Spending on sales taxable items constitute 42.4 percent of total earnings and state taxable income (net income) is about 66 percent of earnings. The state income tax rate is generally 5.0 percent on net income; the first $500 and the next $2,500 are taxed at 2.0 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively, for single persons, head of family, and married persons filing separately while for married persons filing joint returns the first $1000 and the next $5000 are taxed at 2.0 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively. Excess net income is taxed at the 5.0 percent rate. Corporations pay at a 6.5 percent rate and corporate income tax is quite stable at about 15 percent of individual income tax. Sales tax rates used are 4.0 percent for the state and 5.0 percent for local (combined county and city) jurisdictions for a total of 9.0 percent. Local sales tax rates vary between 3.0 to 7.0 percent among Alabama counties, but are most frequently at 5.0 percent. State law in 2006 increased the individual income tax threshold by increasing the standard deduction for taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $30,000 or less and by increasing the dependent exemption for taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $100,000 or less. The Education Trust Fund (ETF) portion of state income and sales taxes is determined. Alabama residents pay a host of other taxes and fees, but sales and income taxes are the largest components of taxes paid. The combined income and sales tax revenues share of total state tax receipts is thus used to determine the maximum total state tax revenue lost for each scenario and a similar derivation is made for the ETF.

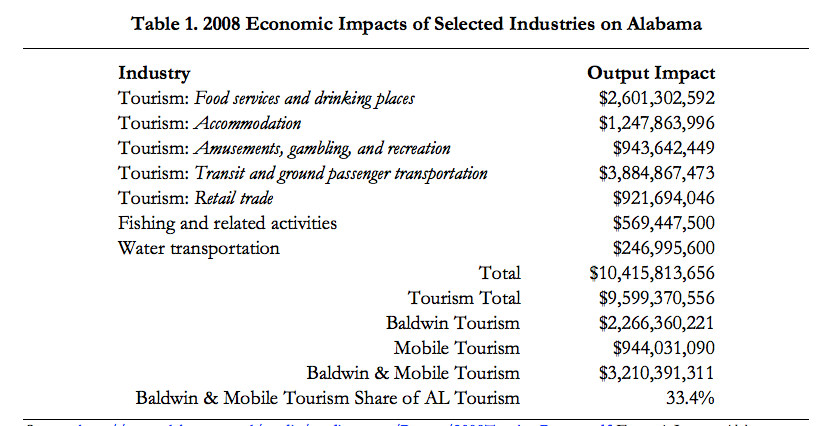

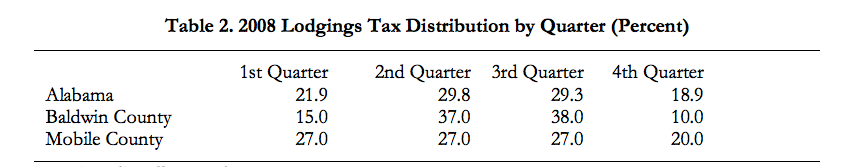

Table 1 shows the 2008 economic impacts of Alabama tourism, fishing, and water transportation on the state. Tourism activities take place within the five industries listed first, but do not account for all of those industries’ impacts on the state; only the tourism component impacts are shown. Tourism in 2008 had a $9.6 billion impact on Alabama, with $3.2 billion or 33.4 percent coming from the two Gulf Coast counties, Baldwin and Mobile. This suggests that the absolute theoretical worst case for Alabama tourism is a 33.4 percent impact loss. Using RIMS II multipliers we estimate impacts of $569.5 million for fishing and $247 million for water transportation. Alabama would have taken a $10.4 billion hit if the oil spill had wiped out all the impacts in the table. Water transportation was not affected to our knowledge, fishing lost at least one major season out of two annually, and tourism was not wiped out—although it was severely impacted—in the two coastal counties. Mardi Gras occurred before the spill, other inland tourism activities continued, and cleanup activities following the spill provided some income generating opportunities for fishermen. Table 2 shows that the explosion of the rig and the capping of the well took place in the two quarters that provide most lodgings tax revenues for Alabama and its coastal counties. We used the lodgings tax distribution to come up with the “somewhat likely” scenario while holding fishing losses at the “worst case” 80 percent level. The “very likely” scenario allows for a salvaging of one major fishing season for a 50 percent loss and half the worst case tourism loss. The “optimistic” scenario halves the tourism loss in the “very likely” scenario while keeping the fishing loss level.

The macroeconomic impacts for each scenario of loss in 2010 are shown in Table 3. In the worst case we adjust theoretical maximum losses of 33.4 percent to tourism and 100 percent to fishing and allow for some tourism and fishing activities prior to the explosion of the rig as well as income generated from cleanup activities to arrive at a 30 percent tourism loss and 80 percent fishing loss. Under this scenario, the oil spill results in losses of $3.3 billion in Alabama economic output, $971 million in earnings, and nearly 49,000 jobs for 2010. Accompanying fiscal impacts are reduced revenues of $46.1 million in local sales tax, $36.8 million in state income tax, and $36.9 million in state sales tax. Of the combined $73.7 million in state income and sales taxes, $67.4 million will be lost to the ETF. State income and sales taxes constitute 72 percent of total state tax collections and suggest that the state could see a maximum loss of $102.8 million if proportionate reductions in all other state tax revenues occur. Similarly, income and sales taxes constitute 92 percent of ETF receipts and thus the fund could see a maximum loss of $73.7 million. The direct loss amount that results in these impacts is $1.6 billion and thus individuals and businesses could make claims totaling that amount. This direct claim amount would be for lost revenues and income and also any damage to property, but not for other tangible or intangible environmental, ecological, and noneconomic quality of life impacts. State and local governments could make a combined $149 million claim for lost tax revenues.

The somewhat likely case of a 20 percent tourism net loss and 80 percent fishing net loss in 2010 results in adverse impacts of (i) $2.4 billion in economic output, $683.4 million in earnings, 33,790 jobs, $31.5 million in local sales tax, $51.1 million in state income and sales taxes as part of a possible $71.3 million total in state tax receipts, $46.8 million in ETF income and sales tax receipts with a possible maximum of $51.1 million to the fund and (ii) claims of $1.1 billion for individuals and businesses and $102.8 million for state and local government.

The very likely scenario of a 15 percent tourism net loss and 50 percent fishing net loss in 2010 yields adverse impacts of (i) $1.7 billion in economic output, $498.9 million in earnings, 24,880 jobs, $23.3 million in local sales tax, $37.6 million in state income and sales taxes as part of a possible $52.4 million total in state tax receipts, $34.4 million in ETF income and sales tax receipts with a possible maximum of $37.6 million to the fund and (ii) claims of $822.2 million for individuals and businesses and $75.8 million for state and local government. In the optimistic case of a 7.5 percent tourism net loss and 50 percent fishing net loss, the impacts are reductions of $1.0 billion in economic output, $283.6 million in earnings, 13,597 jobs, $12.4 million in local sales tax, $20.6 million in state income and sales taxes as part of a possible $28.8 million total in state tax receipts, $18.9 million in ETF income and sales tax receipts with a possible maximum of $20.7 million to the fund, and claims of $462.5 million for individuals and businesses and $41.2 million for state and local government.

Conclusions

In this report we have attempted to provide some sense of the effect of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill on Alabama for 2010 under four different scenarios. The scenarios considered suggest that the oil spill may have reduced Alabama’s economic output by $1.0 billion to $3.3 billion in 2010 and involved losses of $284 million to $971 million in earnings and 13,600 to 49,000 jobs. Individuals and businesses could make direct claims for lost revenues, income, and property damage of between $463 million and $1.6 billion and a combined claim of $41 million to $149 million can be made for lost state and local tax revenues. We considered only macroeconomic impacts and not (i) micro impacts that businesses and individuals can use for making claims or (ii) environmental, ecological, and noneconomic quality of life impacts that contribute to determining the full effects of the disaster.

The oil spill is the largest in U.S. history and its effects are expected to last a number of years. Future year impacts will depend on additional information gained over time about the nature of the disaster and the response to it as well as the combined environmental, ecological, and quality of life effects of the spill and response. Such information will reduce the uncertainty regarding the disaster’s 2010 and subsequent years’ macroeconomic impacts. It is important to note that the impacts presented in this report are preliminary, but can assist in understanding the disaster’s effects while providing information that can help the state make claims for lost tax revenue for the year of the spill.

Samuel Addy, Ph.D. and Ahmad Ijaz

Center for Business and Economic Research

Culverhouse College of Commerce and Business Administration

The University of Alabama

June 2011

Summary

Introduction

The state of Alabama was hit by dozens of tornadoes on April 27, 2011 mainly in central and northern parts of the state that resulted in 240 lives lost and more than 2,200 injured to date. The resulting damage was so severe that 43 of the state’s 67 counties have been declared federal disaster areas. Several communities had major damage and a few had almost complete devastation. Nearly 14,000 homes were either totally destroyed or have been declared uninhabitable. Within urban communities, Tuscaloosa County was one of the worst hit, where an EF-4 tornado with winds of over 190 mph cut a path six miles long and half a mile wide through the middle of the city, completely leveling numerous businesses and residential communities. It is still quite early to fully comprehend the total economic effects of the damage caused by the tornadoes. However, enough information is now available to permit some preliminary estimates of damage effects on the Alabama economy with specific focus on employment, earnings, state finances, and gross domestic product (GDP).

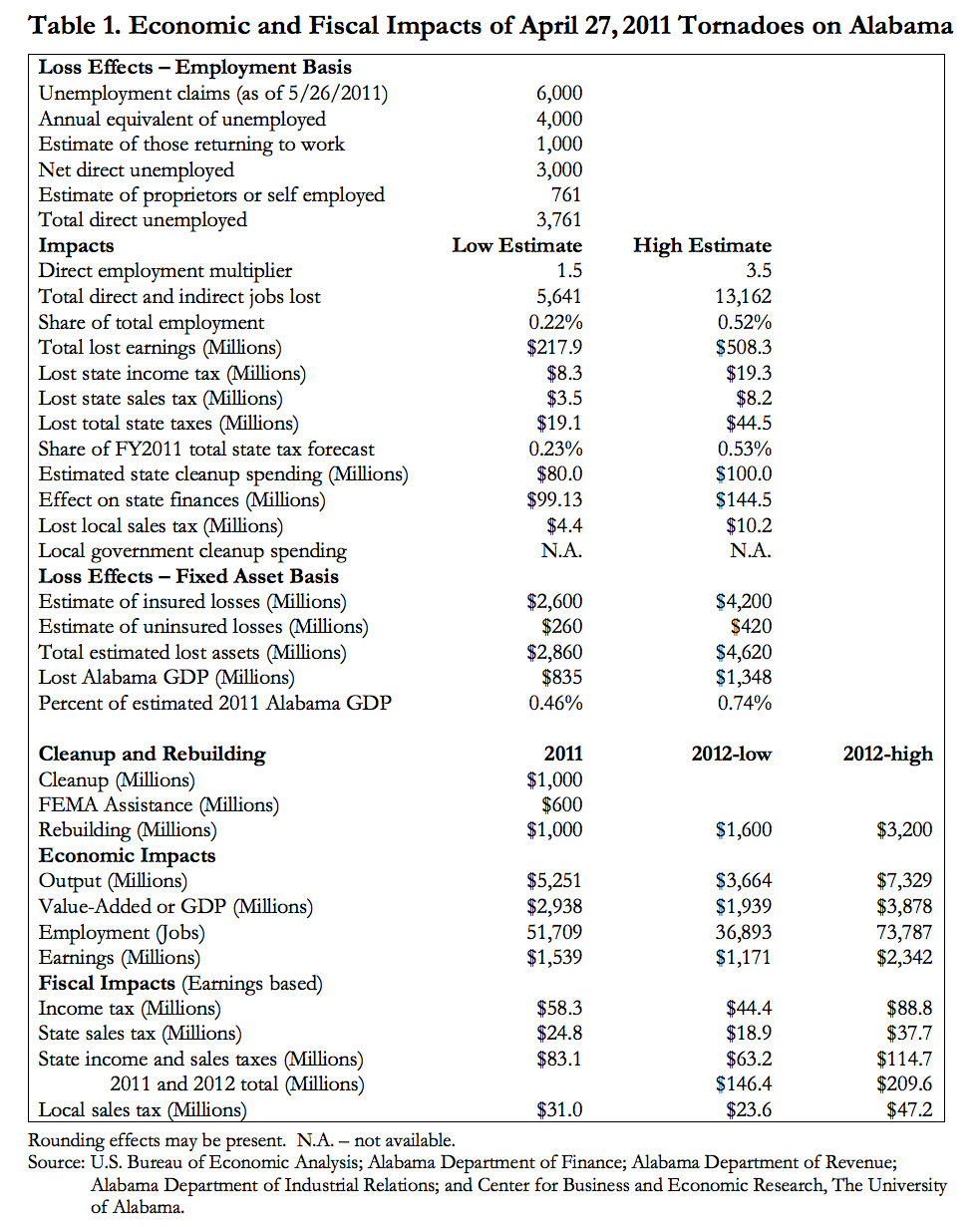

The purpose of this brief report is to present preliminary estimates of the economic and fiscal impacts of the tornadoes as well as the consequent recovery efforts on Alabama. Table 1 shows the preliminary impact analysis results. Multipliers obtained from the Regional Input-Output Modeling System (RIMS II), which was developed and is maintained by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), were used in a model developed specifically for this analysis. To allow for uncertainty regarding the damage impacts at this early stage, low- and high-end estimates are presented. For impacts of recovery activities (cleanup, assistance, and rebuilding), multipliers used were for waste management and remediation services, accommodation, and construction industries.

Fiscal impacts are derived from the earnings impacts allowing for the fact that not all of the earnings impacts are sales or income taxable. Spending on sales taxable items constitute 42.4 percent of total earnings based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data and state taxable income (net income) is about 66 percent of earnings. Sales tax rates used are 4.0 percent for the state and 5.0 percent for local (combined county and city) jurisdictions for a total of 9.0 percent; local sales tax rates vary between 3.0 to 7.0 percent but are usually at 5.0 percent. The state income tax rate is essentially 5.0 percent on net income; the first $500 and the next $2,500 are taxed at 2.0 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively, for single persons, head of family, and married persons filing separately while for married persons filing joint returns the first $1000 and the next $5000 are taxed at 2.0 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively, and excess net income is taxed at the 5.0 percent rate. Corporations pay at a 6.5 percent rate and corporate income tax averages about 15 percent of individual income tax. State law in 2006 increased the individual income tax threshold by increasing the standard deduction for taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $30,000 or less and by increasing the dependent exemption for taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $100,000 or less.

State sales and income taxes are the largest components (constituting about 62 percent) of total state tax collections; residents and businesses pay a host of other taxes and fees. The combined income and sales tax revenues share of total state tax receipts was used to determine the total lost state tax revenue for the damage impact analysis because job losses occurred across many different industries. No such determination is made on the recovery impacts because of the focus on just three industries; only sales and income taxes are reported and as such the recovery fiscal impacts are conservative.

This report would not have been possible without data from Alabama Department of Finance, Alabama Department of Industrial Relations (ADIR), Alabama Department of Revenue (ADOR), BEA, BLS, and newspaper reports. Many thanks are due to these agencies and newspaper publishers and also to our colleagues who assisted with completing this work. Major assumptions in the analysis are that:

Tornado Damage Impacts

Toward the end of May 2011, ADIR had received 6,000 claims for tornado-related unemployment and had data showing that some claimants were returning to work. Adjusting this number of claims received for the eight months remaining in the year after the devastation yields an annual equivalent of 4,000 unemployed. Assuming that a quarter of the claimants will return to work gets the number down to 3,000 net direct unemployed wage and salary workers. To this number we add a 761 estimate for proprietors or self employed based on BEA data and determine that the total direct number of unemployed due to the tornadoes is 3,761 for 2011. It is expected that these people will be working again in 2012.

The 3,761 direct unemployed must be added to tornado-related indirect employment to determine a total employment impact. Since businesses in numerous industries suffered the damages, it is improper to apply specific industry multipliers when that information is not currently available. Most Alabama industries’ direct effect employment multipliers are between 1.5 and 3.5 and so we used these multipliers to determine that the total direct and indirect number of tornadorelated unemployed is between 5,641 and 13,162. This is about 0.2-0.5 percent of total employment including proprietors. Average earnings for workers in 2011 are not much different from the 2009 earnings per worker level of $38,621, which means that $217.9-508.3 million in total earnings will be lost in 2011 because of the tornadoes. This translates into $19.1-44.5 million in lost state taxes, about 0.2-0.5 percent of the total. The lost state taxes comprise $8.3-19.3 million in income tax, $3.5-8.2 million in sales tax, and $7.3-17.0 million in other taxes. In addition, the state is expected to spend $80-100 million on cleanup and so for 2011 the tornadoes will cost the state $99.1-144.5 million. Local sales tax collections will also fall by $4.4-10.2 million in addition to whatever local governments have to spend on cleanup.

A fixed-asset basis is used to estimate the effect on Alabama GDP with the assumption that the state has the same GDP to fixed assets ratio of 29.2 percent as does the nation. Newspapers have reported a range of $2.6-4.2 billion expected insurance claims based on early estimates by Risk Management Solutions and AIR Worldwide. Assuming that the claims cover fixed assets only and allowing 10 percent extra for uninsured losses results in total estimated lost assets of $2.9-4.6 billion and a tornado-related 2011 Alabama GDP loss of $835 million to $1.3 billion or 0.5-0.7 percent.

The economic damage impacts are only a part of the full tornado damage impacts. There are other adverse effects on quality of life that we do not consider because these are non-market or non-economic effects. Examples include lives lost, displacement, mental and physical health issues, and the disruption to the lives of people who were not direct victims. Such quality of life aspects cannot be expressed with the variables used for impact analysis. In short, the damage impacts reported here are conservative.

Impacts of Recovery Activities

Based on the previously mentioned major assumptions, recovery activities will inject $2.6 billion into the Alabama economy in 2011 and $1.6-3.2 billion in 2012. The 2011 spending will create a $5.3 billion output or gross sales impact which includes a gain of $2.9 billion to the state’s GDP. Of the $2.9 billion value-added or GDP impact, $1.5 billion is earnings to 51,709 workers or $29,763 per worker. State income tax of $58.3 million and sales tax of $24.8 million for a total of $83.1 million will be generated along with local sales tax of $31.0 million. In 2012 the $1.6-3.2 billion spending on rebuilding will yield $3.7-7.3 billion in gross economic activity including a $1.9- 3.9 billion contribution to GDP. The earnings impact is $1.2-2.3 billion for 36,893-73,787 jobs at an average of $31,741 per job. Taxes generated are $63.2-126.5 million for the state ($44.4-88.8 million income tax and $18.9-37.7 million sales tax) and $23.6-47.2 million local sales tax.

Clearly the economic impacts of recovery activities are larger than those of the tornado damages. Some of the jobs created by recovery activities might go to people who became unemployed as a result of the tornadoes. It is important to note that the net effect is positive because most of the recovery funds are from external sources—the federal government and insurance claims. Those funds would have gone to some other use if the tornadoes had not struck or caused the devastation. As such, from a national perspective, the combined impact is negative. Additionally, there are the previously mentioned adverse effects on quality of life that if considered and valued could point to a net negative impact. If instead of rebuilding, the opportunity is taken to reinvest the net effect over time could turn positive. A specific example is just replacing a destroyed apartment building with (i) what was preexisting or (ii) something ranging from a larger (more units) and more energy efficient building to a totally different but better use of the space. The second choice is what will facilitate long term positive impacts.

Conclusions

For the Alabama economy, the April 27 tornadoes will initially reduce (i) GDP by $835 million to $1.3 billion or 0.5-0.7 percent, (ii) employment by about 5,600-13,200 jobs or 0.2-0.5 percent, (iii) state tax collections by $19.1-44.5 million or 0.2-0.5 percent, and (iv) local sales tax receipts by $4.4-10.2 million in 2011. Recovery activities (cleanup, assistance, and rebuilding) should pump $2.6 billion into the state economy in 2011 and $1.6-3.2 billion in 2012; state spending of about $80-100 million for cleanup in 2011 is expected. The federal government and insurance claims will fund most of the recovery. Cleanup and assistance should be completed in 2011, but rebuilding will continue into 2012.

Recovery activities will create economic impacts that exceed those of the tornado damage. For 2011 recovery impacts include gains of $2.9 billion in GDP or 1.6 percent, 51,700 jobs with $1.5 billion in earnings for an average of $29,763 per worker, $83.1 million in state income and sales taxes, and $31.0 million in local sales tax collections. The 2012 rebuilding impacts are 36,893-73,787 jobs with $1.2-2.3 billion in earnings or $31,741 per worker, $1.9-3.9 billion in GDP, $63.2-126.5 million in state income and sales taxes, and $23.6-47.2 million in local sales tax receipts.

Over the two years, recovery activities will generate enough revenue to cover damage-induced losses to state finances as well as the state spending for cleanup if assumptions on losses and spending hold. While the tornadoes’ damages are largely localized, the economic impacts of the ensuing recovery activities will be more widespread. Some areas were so devastated that it is nearby communities that will benefit from the recovery spending. This report focuses only on the identified economic effects, and not on other very important quality of life factors such as lives lost, displacement, mental and physical health issues, and disruption to the lives of people who were not direct victims. Incorporating these other factors and the opportunity cost of recovery spending leads to the conclusion that the tornadoes could have had a net negative effect on the state; the effect nationally is definitely negative. Overcoming this negative effect will require going beyond rebuilding to reinventing and reinvesting.