Samuel Addy, Ph.D.

Senior Research Economist, Center for Business and Economic Research

Associate Dean for Economic Development Outreach, Culverhouse College of Business

The University of Alabama

From an economic perspective, taking action at every level of government to facilitate or ensure that businesses survive the COVID-19 pandemic is good and proper economic development. Businesses are important institutions for economies and they generate revenues for governments, especially local ones, while providing services and producing goods. Businesses that do not survive the pandemic will have to be rebuilt afterward, but rebuilding is more costly than providing assistance (with incentives) to enable survival. In normal times, use of economic development incentives focuses on growth, but these are not normal times. Fortunately, local governments in Alabama can use the state’s Amendment 772 to support local business survival since it is in the public interest to do so. After all, if local businesses do not survive, residents will have to go farther to get the products and services those businesses used to provide and the associated revenues will flow to other areas. Additionally, shrinking or declining economies have reduced attractiveness to economic development prospects and residents can choose to move to the places that have the businesses whose services and products they need or want.

Experience with the COVID-19 virus is clearly showing that conducting business as usual is impossible in this or any other pandemic. To mitigate spreading of the virus—especially since medical tests, supplies, and equipment for dealing with the pandemic are currently inadequate—nonessential business shutdown and stay-at-home responses have been implemented. These responses reduce demand for many products and services and will cause output of practically all sectors of the economy to decline during this time. People, institutions people create to make economies function, and natural resources (some of which are converted to structures, equipment, and infrastructure) comprise economies. People are on both the demand side as consumers and the supply side as workers, innovators and entrepreneurs, investors, proprietors, providers, etc. Consequently, by endangering people’s lives and health, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing substantial harm to both demand and supply sides of every economy. Unlike natural disasters where recovery is the focus of responses, pandemics place economies in survivalmode for both people and the institutions (businesses, medical, educational, defense, etc.) used in normal economic times. As such, the proper response to pandemics is to use resources to address survival first, recovery next, and development later.

Since we are in the survival phase, local Alabama governing bodies could use Amendment 772, when and where applicable, to provide “survival assistance” to existing businesses. The amendment authorizes local governments to use incentives for economic development (broadly defined to include industrial, commercial, and public development) so long as certain legal requirements are satisfied. To benefit other parties, this authority permits, (i) using public funds to purchase and/or develop property; (ii) conveying such property; (iii) lending the governing body’s credit or granting public funds; and (iv) borrowing to do the three foregoing activities. The expenditure of funds must be determined to serve a public purpose. As explained earlier, using incentives to address existing business survival during a pandemic serves a public purpose. After the survival phase, these businesses will contribute to local economies again and local governing bodies can return to using incentives solely with a focus on growth.

How much assistance?

How much should the local assistance be? Local governing bodies can decide this on a case-by-case basis recognizing the unique role of each business seeking assistance or apply a set rule to all applications. One straightforward decision rule is to apply a set percentage rate to the direct local taxes generated at the establishment in the previous year. This set percentage rate can be at, above, or below 100 percent. Considering the assistance in the same way as for a fresh recruitment or expansion is proper in recognition of the fact that during the pandemic businesses may not be operating. However, for existing businesses with active incentives lower percentage rates may be applied. The following is an example that applies a 100 percent rate for three different establishments seeking local assistance with normal annual operations as follows: (i) a 40-room, $100 a night, 68% occupancy hotel with 15 workers; (ii) a store with 12 employees and $1 million sales; and (iii) a restaurant with sales of $1 million and 20 workers.

|

Hotel |

Store |

Restaurant |

| Sales at establishment |

$992,800 |

$1,000,000 |

$1,000,000 |

| Direct local (city and county) taxes |

|

|

|

| Sales |

|

$50,000 |

$50,000 |

| Lodgings |

$69,496 |

|

|

| Local COVID-19 assistance (100% of direct taxes, 1 year) |

$69,496 |

$50,000 |

$50,000 |

| NPV (After 5 regular years of operating, 3% discount rate) |

$241,529 |

$173,772 |

$173,772 |

| ROI (After 5 regular years of operating) |

348% |

348% |

348% |

The assistance that each business gets is nearly $69,500 for the hotel and $50,000 each for the store and restaurant. The net present value (NPV) of the assistance and five years of regular yearly direct taxes is about $241,500 for the hotel and $173,800 each for the store and restaurant. The resulting return on investment (ROI) for the local government is 348 percent. Tax revenues and assistance are for both the county and municipality involved in the example. Separate contributions to the assistance can easily be determined using the distribution of the direct tax collections between the two governing bodies or the applicable tax rates. For example, if the city and county sales tax rates are 3 percent and 2 percent, respectively, then the city contributes 60 percent of the assistance and the county contributes 40 percent.

While determining the assistance as shown in the foregoing is straightforward, it does not take into consideration the fact that economic activities have both direct and indirect effects because of interactions with local clients, suppliers, and workers. The loss of any of these establishments will result in more than their direct effects in the local economy. To determine the comprehensive impacts of the establishments requires economic impact analysis, which incorporates economy- and industry-specific multipliers in models that also provide fiscal impacts. Two popular software sources of multipliers are (i) RIMS II, the Regional Input-Output Modeling System software developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and (ii) IMPLAN, which originated from another federal agency.

The table below shows impacts for the same three establishments that are determined using RIMS II multipliers in an economic and fiscal impact model of an Alabama county. The economic impacts focus on output, value-added, earnings (wages and salaries), and employment. Output refers to gross business sales and includes value-added, which is the contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) or the value of goods and services produced on a value-added basis. Earnings impacts are part of value-added and are the wages and salaries of the workers recognized by the employment impact. The fiscal impacts are conservative because just the major and relevant taxes (sales, property, and lodgings) are considered; for some areas, income taxes may need to be determined as well. Applying the same 100 percent to the fiscal impacts, the assistance that each business gets is about $97,400 for the hotel, $71,600 for the store, and $78,600 for the restaurant. The net present value (NPV) of the assistance and five years of regular yearly direct taxes is about $338,500 for the hotel, $249,000 for the store, and $273,200 for the restaurant; the resulting ROI is 348 percent.

The assistance that each business gets is nearly $69,500 for the hotel and $50,000 each for the store and restaurant. The net present value (NPV) of the assistance and five years of regular yearly direct taxes is about $241,500 for the hotel and $173,800 each for the store and restaurant. The resulting return on investment (ROI) for the local government is 348 percent. Tax revenues and assistance are for both the county and municipality involved in the example. Separate contributions to the assistance can easily be determined using the distribution of the direct tax collections between the two governing bodies or the applicable tax rates. For example, if the city and county sales tax rates are 3 percent and 2 percent, respectively, then the city contributes 60 percent of the assistance and the county contributes 40 percent.

While determining the assistance as shown in the foregoing is straightforward, it does not take into consideration the fact that economic activities have both direct and indirect effects because of interactions with local clients, suppliers, and workers. The loss of any of these establishments will result in more than their direct effects in the local economy. To determine the comprehensive impacts of the establishments requires economic impact analysis, which incorporates economy- and industry-specific multipliers in models that also provide fiscal impacts. Two popular software sources of multipliers are (i) RIMS II, the Regional Input-Output Modeling System software developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and (ii) IMPLAN, which originated from another federal agency.

The table below shows impacts for the same three establishments that are determined using RIMS II multipliers in an economic and fiscal impact model of an Alabama county. The economic impacts focus on output, value-added, earnings (wages and salaries), and employment. Output refers to gross business sales and includes value-added, which is the contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) or the value of goods and services produced on a value-added basis. Earnings impacts are part of value-added and are the wages and salaries of the workers recognized by the employment impact. The fiscal impacts are conservative because just the major and relevant taxes (sales, property, and lodgings) are considered; for some areas, income taxes may need to be determined as well. Applying the same 100 percent to the fiscal impacts, the assistance that each business gets is about $97,400 for the hotel, $71,600 for the store, and $78,600 for the restaurant. The net present value (NPV) of the assistance and five years of regular yearly direct taxes is about $338,500 for the hotel, $249,000 for the store, and $273,200 for the restaurant; the resulting ROI is 348 percent.

| Input Data |

Hotel |

Store |

Restaurant |

| Sales at establishment |

$992,800 |

$1,000,000 |

$1,000,000 |

| Operation employment (jobs) |

15 |

12 |

20 |

| Annual payroll (does not include benefits) |

$405,000 |

$300,000 |

$420,000 |

| Economic Impacts (direct and indirect) |

|

|

|

| Output (Gross Business Sales) |

$2,948,408 |

$2,296,254 |

$2,830,432 |

| Contribution to GDP |

$1,823,044 |

$1,435,655 |

$1,563,780 |

| Earnings (Wages and Salaries) |

$658,571 |

$510,720 |

$675,612 |

| Employment (Jobs) |

21 |

17 |

26 |

| Fiscal Impacts (direct and indirect) |

|

|

|

| Local (city and county) taxes |

|

|

|

| Sales |

$13,962 |

$60,827 |

$64,323 |

| Property |

$13,933 |

$10,805 |

$14,293 |

| Lodgings |

$69,496 |

$0 |

$0 |

| Combined local taxes |

$97,390 |

$71,632 |

$78,616 |

| Local COVID-19 assistance (100% of direct taxes, 1 year) |

$97,390 |

$71,632 |

$78,616 |

| NPV (After 5 regular years of operating, 3% discount rate) |

$338,473 |

$248,953 |

$273,225 |

| ROI (After 5 regular years of operating) |

348% |

348% |

348% |

Note: Rounding errors may be present.

Conclusion

Local government use of Alabama Amendment 772 to provide assistance to existing local businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic is prudent. This is because the cost of rebuilding existing businesses that do not survive the pandemic is far higher than providing such assistance to ensure survival. The local support will facilitate eventual recovery and development when the pandemic is controlled; incentive use can then return to focusing on growth purposes only as is normally done with application to new and expanding businesses.

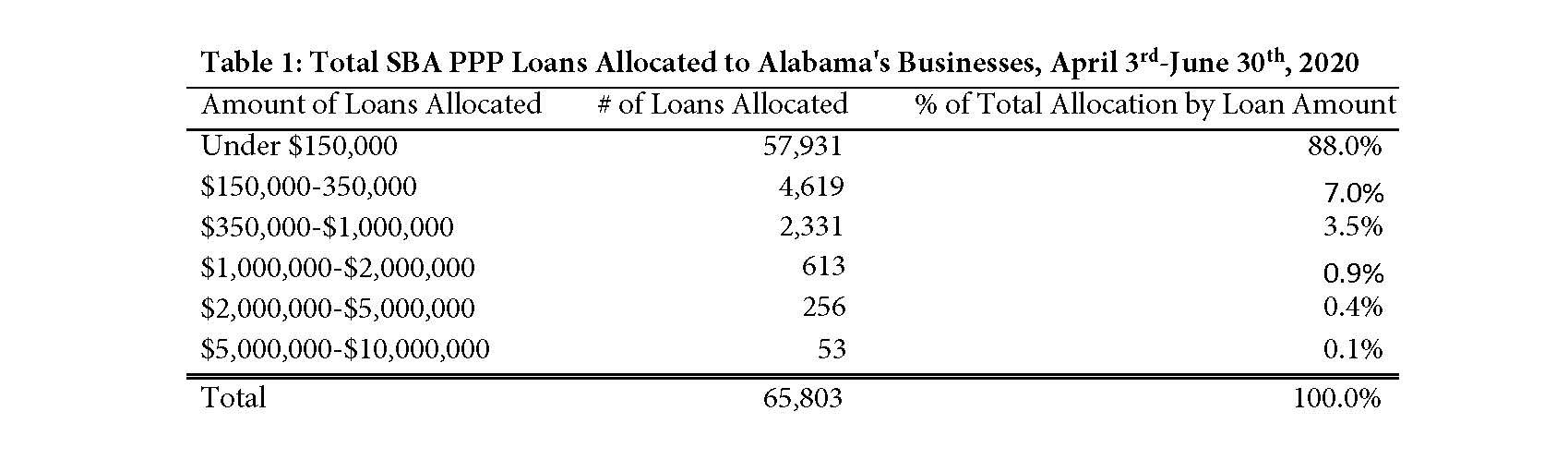

Overall, the loans were not limited to one industry according to the NAICS¹ codes reported on loan applications. A large proportion (57.2%) of all loans allocated to businesses in Alabama were distributed to five broadly-defined industries: other services² (13.0%); retail trade (12.0%); professional, scientific, and technical services (12.0%); health care and social assistance (10.4%); and construction (9.8%). However, there is heterogeneity within each industry classification, and a further disaggregation of the data shows that almost 15% of all loans went to five specifically-defined industries: full-service restaurants (2,158); law offices (2,016); doctor offices (1,956); religious organizations (1,874); and real estate agencies (1,769). The loans were not limited to for-profit business, as almost 5% of PPP loans were allocated to non-profits in the state. In addition, more than a majority (57.6%) of jobs retained from PPP funding were in only five of the following broadly-defined industries: health care and social assistance (14.1%); accommodation and food services (12.1%); retail trade (11.1%); manufacturing (10.4%); and construction (9.9%).

Overall, the loans were not limited to one industry according to the NAICS¹ codes reported on loan applications. A large proportion (57.2%) of all loans allocated to businesses in Alabama were distributed to five broadly-defined industries: other services² (13.0%); retail trade (12.0%); professional, scientific, and technical services (12.0%); health care and social assistance (10.4%); and construction (9.8%). However, there is heterogeneity within each industry classification, and a further disaggregation of the data shows that almost 15% of all loans went to five specifically-defined industries: full-service restaurants (2,158); law offices (2,016); doctor offices (1,956); religious organizations (1,874); and real estate agencies (1,769). The loans were not limited to for-profit business, as almost 5% of PPP loans were allocated to non-profits in the state. In addition, more than a majority (57.6%) of jobs retained from PPP funding were in only five of the following broadly-defined industries: health care and social assistance (14.1%); accommodation and food services (12.1%); retail trade (11.1%); manufacturing (10.4%); and construction (9.9%).