Total Federal Expenditures Rise Slightly in Alabama in FY 1996

- August 6th, 2019

Total Federal Expenditures Rise Slightly in Alabama in FY 1996

In fiscal year 1996, the federal government spent $23.409 billion in Alabama. That amounts to an average of $5,478 for every resident of the state, well above the $5,180 U.S. average. Federal expenditures in Alabama rose 3.04 percent over 1995, while, for the nation as a whole, spending was up 2.24 percent.

Spending by the Department of Defense totaled $4.083 billion in FY 1996, 17.4 percent of all federal spending in Alabama and higher than the 16.7 percent U.S. average. Defense spending was down from the 1995 total of $4.136 billion, paralleling a national decline.

Federal expenditures are broadly grouped into four main areas: salaries and wages, procurement, direct payments, and grants. From fiscal year 1995 to 1996, federal spending in three of the four categories fell, even when expressed in current dollars. The overall picture was helped by a 7.6 percent increase in direct payments for individuals. Direct payments totaled $13.616 billion in 1996, or 58.2 percent of all federal expenditures in the state. This includes $5.758 billion in social security payments for retirement, survivors insurance, and disability. Medicare payments in Alabama totaled $3.470 billion, while federal retirement and disability payments approached $1.689 billion.

Salaries and wages brought almost $2.898 billion into the state in fiscal year 1996, lower than the $2.960 billion spent in 1995, as federal employment in Alabama declined by over 2,000 from 1995 to 1996. Procurement contracts added $2.937 billion, with 62.6 percent of purchases made by the Department of Defense. Procurement totaled $3.059 billion in FY 1995.

Grants to state and local governments in Alabama amounted to $3.325 billion, down from $3.419 billion in FY 1995. The biggest component was Medicaid payments totaling $1.455 billion. In addition, expenditures by the Department of Health and Human Services included $254.2 million for social services block grants, child and family services, and AFDC. And the child nutrition, food stamp, and WIC programs of the Department of Agriculture sent $292.6 million to the state. Alabama governments also received $308.9 million for community development and housing programs from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

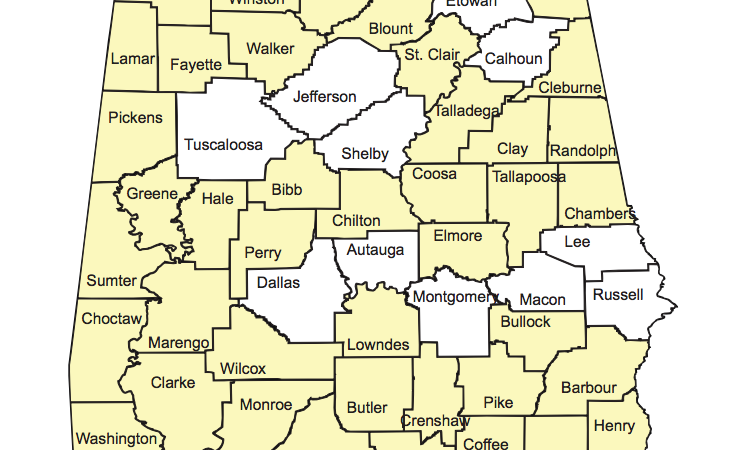

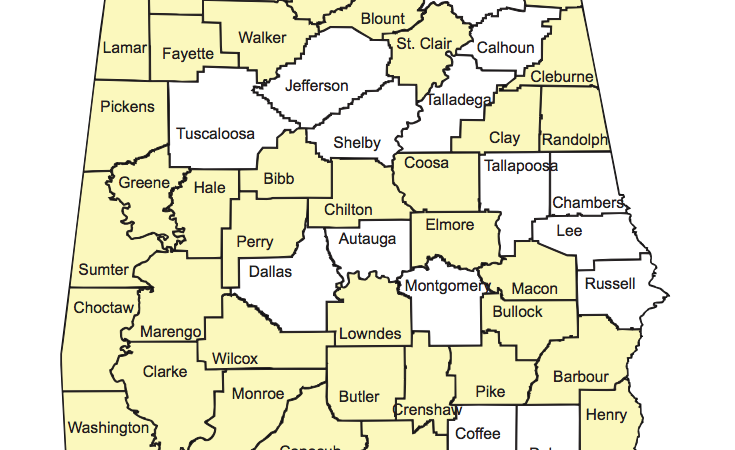

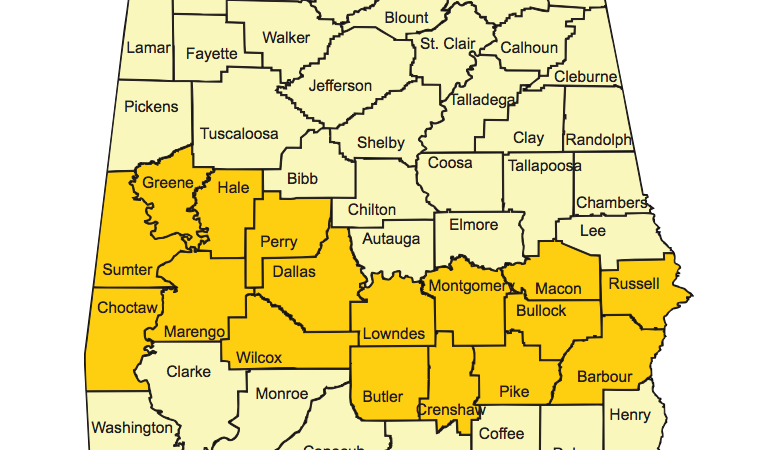

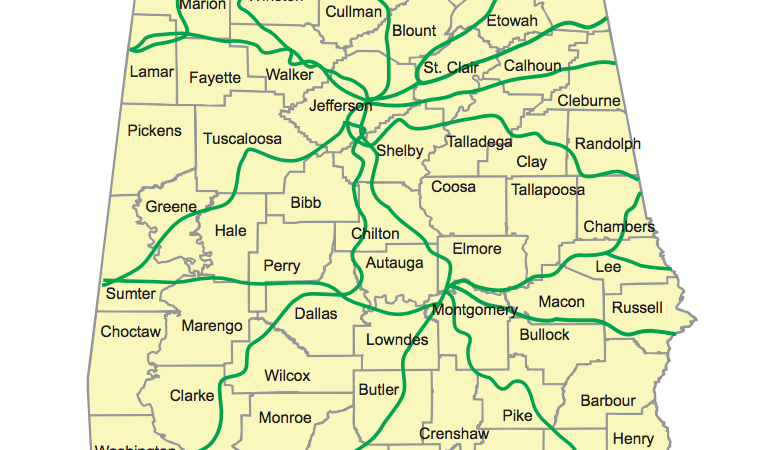

As a state, Alabama ranked thirteenth in 1996 on federal expenditures per capita and fifth in the category of direct payments for individuals. While the state average per capita federal expenditure in 1996 was $5,478, six Alabama counties received over $7,000 per person. These included Calhoun, Coffee, Dale, Macon, Madison, and Montgomery counties.

**06/97